Our History

In the 1760s, the village of Saint Louis resembled a medieval town in Europe. Its habitants lived within the confines of a fortified village and traveled each day to their prairie or cultivation fields, sometimes several miles away. Four major cultivating fields surrounded early Saint Louis: the St. Louis Common Field, Grande Prairie, Cul de Sac Prairie, and Prairie des Noyers. East of the Prairie des Noyers (the present site of the Missouri Botanical Gardens) was another large tract of land known as the Saint Louis Commons. This tract was owned by all the villagers in common for the purposes of cutting firewood, pasturing livestock and hunting game. Never intended to be sold since it was held in common, its boundaries were not fixed because its area expanded as the population of St. Louis grew. Compton Heights occupies the Northwest corner of what was previously the Saint Louis Commons – its initial land partition was received in the 1850s.

This prairie, dotted with springs, limestone outcroppings, and rolling hills first belonged to prominent St. Louisans, including James S. Thomas, George I. Barnett, and Henry Shaw. In 1855, the city limits were expanded to include this area, just Southwest of downtown. The Compton Reservoir was completed in 1871, as the city's population continued to expand.

The Compton Heights subdivision, embracing Hawthorne and Longfellow Boulevards and adjacent blocks between Grand and Nebraska was laid out in 1888 by Julius Pitzman to correct errors he made in designing Vandeventer Place. Several unique features were incorporated into his design. These include gracefully curved streets to create a pleasant vista and reduce traffic flow. The residential deed restrictions, the first in Missouri, ensure private family use of each residence and establish a common setback for each home. This zoning principle, which is now widely accepted, was a new concept at the time and was not upheld by the Missouri Supreme Court for almost three decades.

Many of St. Louis' first families settled in this area; corporate leaders of Anheuser-Busch, Falstaff, Magic Chef, Monsanto Corporation, and Pet Incorporated were among the early founders. A number of the homes still remain in the families of the original builders some 100+ years later.

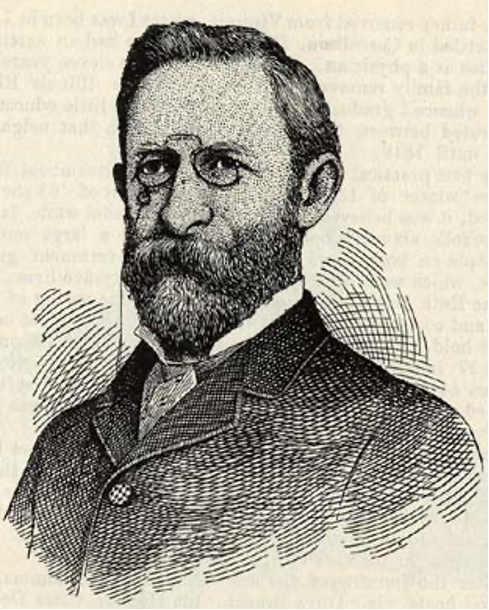

Haarstick & The Compton Hill Improvement Company

Compton Heights is one of the earliest examples of planned residential developments of the American 19th century. The original "Compton Hill Improvement Company" was formed quietly in 1888 with a $400,000 investment (about $10m in today's terms) in the form of $100 shares by 33 individuals. Chief among the investors were Henry C. Haarstick (President of the Board) and Julius Pitzman (Secretary), both of whom lived on Russell Avenue (renamed from "Pontiac" in 1884). By 1890, over $300,000 had been spent in development including "above-street grading for each lot, sewers, gas and electric light, water, Telford pavements, Granitoid sidewalks, curb and gutter."

When the articles of association were renewed on June 1, 1898, Haarstick dramatically increased his holdings from 150 shares in 1888 to 3,080 shares in 1898, giving him a dominant controlling interest in the Compton Hill Improvement Company. The number of shareholders had dropped from 33 to 7, all of which were members of the board of directors. Pitzman had also increased his holdings from 100 to 250, Herman Haeussler from 100 to 120 shares and Edward C. Kehr from 100 to 150. This new charter would last for 20 years, expiring June 1, 1918.

A Gilded Age entrepreneur whose life reads like a Horatio Alger story, Henry C. Haarstick created an international shipping empire on the banks of the Mississippi River. A razor-sharp financier, he co-founded the Veiled Prophet Ball, at which his great-granddaughter was crowned queen, and established a family that has belonged to the elite St. Louis Country Club for a century. Yet today, few know the Haarstick name, because Henry Haarstick left no male heirs.

The story begins with 13-year-old Heinrich Christian Haarstick. He and his parents left Germany and arrived in St. Louis in 1849. The city was reeling from a cholera epidemic and the great fire that had wiped out the riverfront. But young Haarstick, seized each setback that befell him and bent it into good fortune. In his twenties, he became co-owner of a distillery. It was destroyed by fire shortly thereafter, so he bought out his partners, rebuilt the distillery and sold it, making his first fortune at age 31.

Foreseeing the boom in river traffic, Haarstick next bought the only barge line in St. Louis. As his peers laughed at him, he turned St. Louis & Mississippi Valley Transportation into the largest barge line in America. Barking orders in his thick German accent, he bought out his competitors, opening foreign markets throughout Northern Europe and South America, across the Mediterranean and in the West Indies. No kernel of grain grown in the West went down the Mississippi and out to sea that Henry C. Haarstick did not control. The public accused Haarstick of monopoly, but it was all legal. He went on to make two more fortunes, in a chemical plant and in banking. He and his wife, Elise, were now more than wide-eyed immigrants with newfound wealth; among his papers at the Missouri Historical Society Library is an invitation to dine at the White House. (via Ellen Harris and Sunny Pervil)

You can learn more about the history of the land and early development via Compton Heights: A History and Architectural Guide, which is filled with details and excellent photographs.

Nature As Neighbor & Deed Restrictions

There were two things that made Compton Heights unique among its contemporary subdivisions.

The first was its landscaped, curving streets with lovely vistas designed "to view nature as neighbor not as an enemy to be subjugated by some rectilinear grid.". Julius Pitzman, a surveyor who had designed Benton Place in Lafayette Square and Vandeventer Place, laid out the pleasingly serpentine public streets of Compton Heights ~250 acres in 1889. He named the two main streets for writers Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Pitzman would go on to become a major influence on city planners around the country, designing Forest Park and over 40 other private streets.

The second was the idea of selling lots with deed restrictions – the first in the state of Missouri. Lawyer Ed Kehr, one of the original shareholders, drew up these restrictions which still apply to any lot originally sold by the Compton Hill Improvement Company. In a condensed form, they include:

A building line is established individually from the street and no building or part may extend over, except the steps and platform in front of the main door – and even that may not be more than eight feet.

Only one building, and that a private residence, on any lot. Absolutely no flats or businesses.

The building, with the exception of the portes cochere, may not be closer to the side of the lot than 10 feet.

If a building does not cost at least $7,000 (compared to Westmoreland Place ~$7K and Portland Place ~$6K), the plans must be submitted to the improvement company. No fence or wall can be put on the sidelines for 30 feet back from the building line. The existing grade of the lot for 60 feet from the street cannot be changed more than 12 inches without the consent of the owner of the adjoining lot.

A subsequent successor or buyer will be bound by the same restrictions.

Those deed restrictions would later save the integrity of Compton Heights during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s when large homes in other areas were turned into rooming houses.

Auction & Growth

The first building permit was issued in July of 1890, but by 1893, less than a handful of houses had been built, and 160 lots remained unsold. The CHIC continued to advertise heavily.

In 1896, a cyclone tore a path down Jefferson Street just East of the neighborhood, devastating much of the city in what is generally considered as Saint Louis's deadliest storm on record.

As economic depression and competitive factors hampered the sale of the remaining lots, an auction was held on June 14, 1902 to expedite things.

Although well established by the turn of the century, the largest flurry of construction in Compton Heights centered around the St. Louis World's Fair. The 1904 World's Fair brought much attention to Saint Louis, and Compton Heights grew quickly with the population. The majority of these homes were built by affluent merchants and manufacturers of primarily German descent. By the turn of the 20th Century, immigrants were making money in groceries, beer and industry and they built homes in Compton Heights to show their wealth and taste. Evidence of their German origins lingers in the rounded arches and turrets of the mini-castle-style homes favored by these residents and their architects.

After the lots had sold, the improvement association had become relatively inactive. On June 8, 1921, three years after the charter had expired, a document was registered with the City of Saint Louis for the purpose of winding up the business. The last election for members of the board had been in 1914, and three of the directors had died. The remaining four acted to dissolve the corporation.

Forming the Association

As long as the Compton Hill Improvement Company was in business, it was naturally in their interest to see that the restrictions were enforced. With the liquidation of the company, it was necessary for the residents to band together to enforce the restrictions. A series of "protective associations" came into being. Records are sketchy, and there is some indication that the associations may have started even earlier than 1921.

Judge Julius Muench recalled that he was president of a group organized in the mid-1920s to head off one or more boarding houses that were threatening to establish themselves in the eastern end of the Heights on Milton Boulevard. "At the time we were organized, there was already in existence a sort of protective association for the upper end of the Heights, the part lying west of Compton Avenue. The purpose of this organization was more or less aesthetic. Its purpose was to keep the appearance of the district up to its original standard."

The association fell apart during the early days of World War II. On September 10, 1946, a new association, known officially as "The Compton Heights Improvement Association" was formed to help enforce the deed restrictions and keep the area beautiful. Meetings were originally held in the Liederkranz Club on Grand Avenue (now the site of the Jack-In-The-Box). To the credit of the board, the unique deed restrictions have been tested and upheld multiple times throughout the neighborhood's history, though not all battles have been won.

New bylaws were adopted on December 3, 2003, changing the name to "Compton Heights Neighborhood Betterment Association" (CHNBA) and establishing 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.

More Recent History

Installation of the Tiara

In 1966 some new entrance markers were placed atop the old cast-iron standards. The tiara emblem on the big ornamental iron standard at the Hawthorne-Longfellow wedge was the design of the late Frank T. Hilliker.

Hilliker, an engineer and Compton Heights resident, collaborated with St. Louis artist Rodney Winfield (who designed the stained-glass Space Window in the Washington National Cathedral) on the design, at a cost of $4,000 to the Association. The dedication was postponed because of bad weather, but on April 30, 1966, Mayor A. J. Cervantes was driven in a motorcade around the boundaries of the Association's area, and the musicians of the Roosevelt High School Band played at the wedge (now known as the "Grand Point").

Increasing Diversity

Until 1970, city law prevented same-sex couples from owning homes. Now, about 20 percent of Compton Heights' residents are gay or lesbian.

Historic District

In 1978, Compton Heights was designated a Local Historic District.

Grand Point

When the owner of 3507 Hawthorne expressed her intention to sell her property, the Board set its sights on acquiring part of that property commonly known as the "Grand Point". The property was eventually surveyed and subdivided in such a manner as to set aside much of the green space as a separate lot. Until such time as the Association had the funds to purchase this lot, a group of civic-minded residents stepped forward and financed its purchase.

Eventually, the proceeds of a very successful house tour and individual donations made it possible for the Association to purchase the "Grand Point" from the residents. In December 1998, the property officially became an asset of Compton Heights and is now the staging grounds for many neighborhood events.